What is FSM?

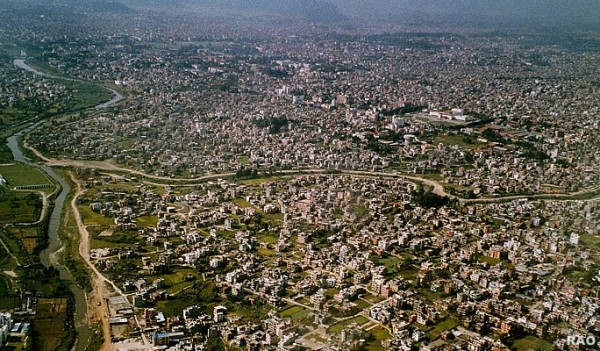

The pace of urbanization and population growth in Nepal has been rapid. According to the 2011 Census, only 17.1 per cent of the total population (26.5 million) lived in 58 municipalities. At present, 62 per cent of people are living in urban areas along with the declaration of 293 municipalities by the government in 2017. This rapid population growth and haphazard urbanization have resulted to an increment in solid waste, faecal sludge and wastewater. The unsafe disposal of this waste has polluted water bodies and the environment posing the threat of many water-borne diseases to public health.

In this context, Faecal Sludge Management (FSM) is a crucial intervention required for safe excreta management and sustainable sanitation. In general, FSM is understood to be only the treatment of faecal sludge. However, treatment is just one of the steps of faecal sludge management. FSM actually includes the entire steps from a proper collection of faecal sludge to its safe disposal or reuse. Five major components of faecal sludge management are: User Interface, Containment, Desludging and Transportation, Treatment and Disposal/Reuse.

| Component | Definition | Objective |

| User interface | Technologies with which the user comes into contact and access the sanitation system | To improve the sanitary conditions in people’s homes. |

| Collection (Containment) | Technologies which enable wastewater to be collected, temporarily stored and, if appropriate, to be partially treated. | To improve the sanitary conditions in people’s homes/institutions. |

| Transportation | Technologies that transport wastewater/faecal sludge away from the user’s home to temporary disposal, treatment or discharge sites. | To ensure the health and hygiene of the people. |

| Treatment | Technologies used to treat wastewater/faecal sludge and residues in order to reduce the pollution load by means of physic-chemical and/or biological processes. | To reduce pollution and ensure the environment and health safety of the community. |

| Disposal/reuse | Technologies or methods by which residues are ultimately disposed of in the environment or reused as useful resources. | To allow safe and adequate disposal of treated residues (disposal) or the utilization of treated residues (reuse). |

Why FSM?

Declaration of open defecation free zones has significantly accelerated the toilet coverage. But this should not be the end goal. The general concept of toilet is limited to the infrastructure or superstructure and flushing systems to get rid of shit from sight. But the projects or programmes should focus on excreta management rather than only toilet construction.

Basically, two common sanitation practices exist in Nepal – one, the sewered system and the other, non-sewered system. 6 per cent of total population use sewered sanitation system and 94 per cent have the non-sewered or on-site sanitation system. Only in Kathmandu Valley, around 70 per cent of the households use sewered system whereas 30 per cent of the households still have on-site systems such as pit latrines or septic tanks (MICS 2014, Nepal).

A study conducted by ENPHO shows that only 7 per cent of the wastewater collected from sewered system is safely disposed after the treatment whereas 93 per cent of wastewater is discharged directly into the river without any treatment. In non-sewered system, the faeces get collected in pits or septic tanks and gets converted into faecal sludge. The faecal sludge thus generated from these systems need regular desludging services. Again, due to lack of treatment systems, the faecal sludge is collected mechanically or manually and disposed haphazardly into water bodies or open spaces or forest.

Thus, ultimately in either case, the faeces are discharged or disposed into the river or open environment. The impact of jeopardizing the environment, river and health remains the same. This means that there is no significant difference between ‘open defecation’ and ‘open discharge or open disposal’. The only difference is the language, technique and practice. We now have toilets but the faeces are not being properly and safely managed. Hence, sanitation is not just about toilet construction. It is crucial to treat and safely dispose the faecal matter. Toilet should not be considered the only solution, and additionally, the entire sanitation value chain needs to be emphasized which includes collection, desludging/transportation, treatment and reuse/safe disposal.

As many households still use pits or septic tanks for excreta disposal, efficiently managing faecal sludge is inevitable to manage the sludge generated from these sanitation systems. Thus, before the situation turns out to be more complex, the issue of faecal sludge needs to be immediately addressed prioritizing for faecal sludge management at all levels.

FSM Status and ENPHO’s Initiatives

FSM is gaining prominence, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas of Nepal. A study conducted by ENPHO shows that 170,000 m3 of faecal sludge is being produced annually from existing on-site sanitation systems and discharged into water bodies by 15 desludging vehicles without any treatment (ENPHO, 2014). Besides, there are many informal service providers (anyone working on daily wage basis) providing this service.

ENPHO has been developing and promoting several initiatives for proper FSM in Nepal.

In 1998, ENPHO provided technical support to establish the first faecal sludge treatment plant at Teku, Kathmandu Metropolitan City. But since 2005, the facility has been out of operation due to various problems.

In 2000, ENPHO provided technical support to establish a large-scale faecal sludge treatment plant in Pokhara.

ENPHO with the support from Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) has also designed an appropriate, low-cost faecal sludge treatment system at Guheshwori and developed an innovative business plan for the system. But, due to some reasons, it has not been implemented.

In 2014, ENPHO collaborated with The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to perform an intensive study on FSM status in Kathmandu Valley and prepare a business plan for FSM in Shreekhandapur.

In 2016, ENPHO in collaboration with Help for Children Beilngries- Kathmandu, Saligram Bal Griha and Mahalaxmi Municipality and with support of BORDA and CDD Society established Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant at Lubhu in Mahalaxmi Municipality.

Similarly, in 2016, ENPHO established another faecal sludge treatment plant in Gulariya, Bardiya in partnership with Practical Action Nepal and Gulariya Municipality.

In 2018, ENPHO with the support of BORDA conducted situational assessment of faecal sludge management in nine Municipalities namely Dhangadhi, Amargadhi, Dakshinkali, Gorkha, Kohalpur, Lalbandi, Shukla Gandaki, Solu Dudhkunda and Godawari and developed faecal sludge status report and factsheets of the Municipalities.

ENPHO, in collaboration with Mahalaxmi Municipality, Kathmandu Valley Water Supply Management Board, Nepal Bureau of Standards and Metrology and other relevant stakeholders, is supporting pilot implementation of ISO 24521 guidelines for the management of basic on-site domestic wastewater services in Mahalaxmi Municipality. This project (January 2019 – June 2021), which is supported by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under grant assistance, is the first of its kind in Nepal and globally.

ENPHO with the support of United Cities and Local Government Asia Pacific (UCLG ASPAC) and in collaboration with Municipal Association of Nepal, Municipal Association of Bangladesh and SNV Netherlands Development Organization is implementing ‘Municipalities Network Advocacy on Sanitation in South Asia’ project (May 2018 – October 2020) to implement the sanitation and investment plans in five pilot Municipalities (Lahan, Dhulikhel, Waling, Lamahi and Bhemdatta) focusing on FSM policies, institutional, financial and regulatory framework.

With the support of various agencies, ENPHO has conducted research and studies related to FSM, provided technical support and organized capacity building training. ENPHO has been actively engaged in research-based policy advocacy to address FSM issues and has significantly supported national and local government agencies in the formulation of FSM policies, plans, by-laws and guidelines. ENPHO further plans to foster collaboration for awareness-raising, policy reforms, building local capacity and innovating effective solutions through research and development to tackle this problem.

The Road Ahead

Two-third of the population of the country is expected to be living in Municipal areas. It is imperative to effectively manage faecal sludge in order to control waterborne diseases and environmental pollution. To address the faecal sludge management issues along with this rapid urbanization, it is crucial to take the necessary steps to move ahead.

Sustainable FSM service is needed to achieve SDG sanitation targets and the leadership role of federal, provincial and local government is vital to achieve these targets.

FSM policies should be formulated, enforced and good demonstrations of sustainable FSM should be scaled-up at local level. Strong coordination is essential amongst municipalities, relevant public services, infrastructure development sectors, public utilities sector, faecal sludge operators and other relevant stakeholders for smooth operation of the services and to avoid resource duplication. An enabling environment should be created for public-private partnership (PPP) opportunities on FSM and this PPP approach should be followed to manage faecal sludge.

Public awareness and outreach campaigns should be increased to educate the people on the importance of faecal sludge collection, desludging/transportation, treatment and disposal or reuse. Rather than taking as a waste, faecal sludge should be seen as resources whether it be for irrigation, as organic fertilizer or generating energy.

FSM requires priority and immediate response from the government and people in the days ahead. FSM should be integrated with other urban sanitation issues. More professionals need to be developed in this sector to fulfil the increasing demand along with the focus on their capacity building. Designing, constructing and implementing the faecal sludge management systems should be context-specific. It should not only focus on infrastructure but should consider the city-wide inclusive sanitation- a new agenda for reaching SDG sanitation targets.